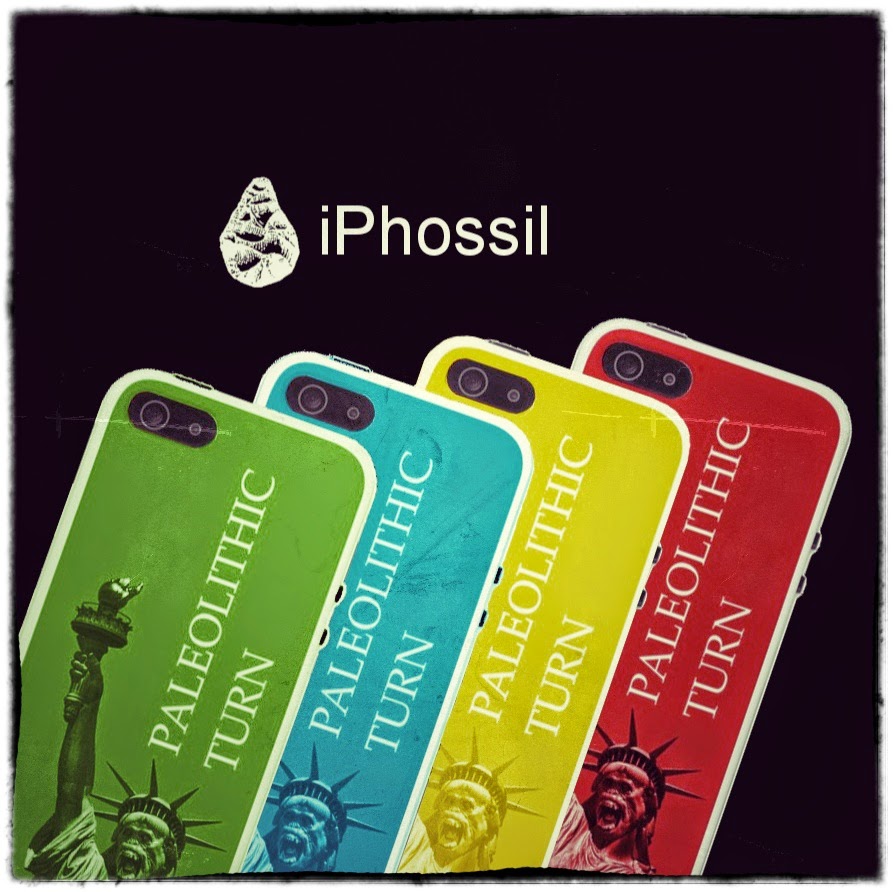

iPhossil

iPhossil

by Francesco Gori

Today’s media, the

up-to-date technologies, are the objective manifestation, the incarnation, the

achievement, if you want, of our childhood dreams. They are the physical trace

left behind by a past imagination: before being actually realized they have

been long imagined.

Science fiction is crucial

to understand this point: it is a literary/cinematographic genre entirely based

on this technical imaginary. This is why, on the left side of the present time,

what has been before imagined, than realized, becomes a fossil, i.e. a “signed”

object, a material thing recording the trace, the inscription of an earlier

imaginary. I started reading of video-phones and video-books when I was a kid,

in the 1990’s; soon I discovered that the books containing this foresights have

been written prevalently during the 1950’s, while their film versions were

contemporary of me (I was born in 1983), being realized starting from the 1980’s

and now became a major cinematographic genre.

Today I do make on a

regular basis video-phone calls and read “ebooks”. Moreover, I myself, as a

blogger, am an ebooks writer. What I do in my everyday life, then, has been

largely imagined – not predicted, but imagined – by people such as

Asimov, Van Voght, Lafferty, and Philip K Dick, who is the precursor of the

cyberpunk sci-fi trend, leaded by William Gibson. In the latter’s Neuromancer

it’s thoroughly outlined the uncanny feeling of being outline for a digital

man. But it’s Asimov, probably, the most

interesting figure among others, being the incarnation of the cold war

cultural climate that made the science fiction genre possible in the first

place: American born Russian with Jew blood in his veins: there you have the

perfect Cold War kid, whose imagination has considerably contributed to shape

the culture of the years to come. And, along with the imaginary, the technology.

What I claim, is that the

so-called “technological determinism” could be reversed upside-down, by

demonstrating, at least from Jules Verne on, how deeply literature and fiction

in general have influenced and oriented the achievements of later science and

engineering. Looking backwards, on the other hand, one can understand why the

newest jewels of contemporary technique end up so soon becoming fossils of a

past age. This is why we should look at the latest iPhone as an iPhossil, bearing

the signature of an age doomed to enter very soon the archive of our cultural

memory: today’s cutting edge technologies are tomorrow’s museum pieces, and the

day-after-tomorrow’s relics of a lost world. In the digital age, the future is

approaching so fast that this process can be experienced within a life time,

making our lives a sanctuary of archaic vestiges, turning our

quickly-obsolescent gadgets into fossils, faded traces of a time as far as the stone

age.

Yesterday, I re-watched The

Matrix (released in 1999) after a good deal of time. The amazement of the

first view had completely disappeared, giving place to a strange feeling of

detachment mixed with some sort of nostalgia. A distance, not only temporal but

even “cultural” had occurred between me and that film as well as between me

today and the 14 years old guy astonished by that movie: I don’t belong anymore

to that age. Take a look at Neo’s cellphone: is it not a museum piece compared

with today’s smartphones? Even further: isn’t it not kind of pathetic that

these guys have to struggle so hard to find a physical place – as a telephone

booth (truly a relic of an ancient age) – where to be “connected”? Our age is

already completely reshaped comparing to the late 1990’s in which the film has

been conceived and realized. Our social relationships and our report with the

physical space is far different from that narrated in The Matrix. Today we can

be “online” everywhere we go, even on the top of an Himalayan peak (an example?

see Simone Moro’s Himalayan expedition on Nanga Parbat:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cUhFWb46wJw) and more and more of our social

and working activities are now disentangled by any physical bind whatsoever.

To watch The Matrix today, then,

means to get in touch with a cultural fossil, a wreck of a past age, a trace of

an older imaginary. Science fiction – especially the cinematographic one – is

particularly interesting from this point of view, since it reveals not only the

technical possibilities of an age, but also, and along with it, shows the

imaginary, the dreams, the hopes and the fears connected to it.

This peculiar feature makes

the literary/cinematographic genre of sci-fi a privileged historical ground for

media theory. “Hisorical” in the sense that it provides an account of the

dreams of a past time and might be helpful, therefore, to de-familiarize

ourselves from the time we live in. A time of sleep, as any cultural present,

as Banjamin has pointed out. His Arcades project was aimed exactly at this

goal: to de-familiarize the reader from his time by means of a metaphorical

procedure (= showing him the sleep and the dreams of a former time) and make

him/her familiarize with his own cultural unconscious, of his own being-asleep.

The task of the intellectual remains always the same, from Socrates (at least)

on: to generate consciousness. It’s an old story to tell: a conscious slave is

freer than an unaware lord.

Going back to our

technological gadgets, then, they

are nothing but the trace of what we where dreaming when we where children,

that’s why they have the disturbing taste of the fulfilled dreams. Nothing

worst can happen to a man than his desires to come true, says Plutarch. In its

very essence, our current technology is the fulfillment of our fathers’ or

grandfather’s desires: we’ve wished for centuries we could fly and eventually

we did: are we happier today? Are

we unhappier? Does it make any difference?

Nessun commento:

Posta un commento